What Group of Women Was Initially Targeted to Join the Labor Force?

Introduction

In almost every state in the globe, men are more likely to participate in labor markets than women. Still, these gender differences in participation rates accept been narrowing substantially in recent decades. In this post nosotros discuss how and why these changes are taking place.

The first section in this commodity provides an overview of the 'stylized facts', including an overview of women'southward participation in the informal economy and unpaid care work. The second department provides an overview of the fundamental factors that accept been driving the broad trends (these factors are farther discussed in a companion blog post).

Before we move on to the details, hither is a preview of the chief points:

- In virtually countries men tend to participate in labor markets more frequently than women.

- All over the world, labor force participation among women of working age increased substantially in the last century.

- In some parts of the world, the historical increase in female labor strength participation has slowed down or even regressed slightly in contempo years.

- Women all over the world allocate a substantial amount of fourth dimension to activities that are not typically recorded as 'economical activities'. Hence, female person participation in labor markets tends to increase when the time-price of unpaid care work is reduced, shared equally with men, and/or made more uniform with marketplace piece of work.

The global picture

Men tend to participate in labor markets more than oft than women

Effectually the globe men tend to participate in labor markets more frequently than women. Yet, it only takes a glimpse of the data to run into that there are huge differences across societies.

The map hither provides a moving picture of how men and women compare today in terms of participation in labor markets, country past land. Shown is the female person-to-male ratio in labor strength participation rates (expressed in percent). These figures show estimates from the International Labor System (ILO). These are 'modelled estimates' in the sense that the ILO produces them afterward harmonizing diverse information sources to amend comparability across countries.

As nosotros tin can come across, the numbers for most countries are well below 100%, which means that the participation of women tends to be lower than that of men. Yet differences are outstanding: in countries such as Syria or Algeria, the ratio is beneath 25%. In contrast, in Laos, Mozambique, Rwanda, Republic of malaŵi and Togo, the relationship is close to, or fifty-fifty slightly in a higher place 100% (i.due east. there is gender parity in labor force participation or fifty-fifty a higher share of women participating in the labor market than men).

Female labor force participation is highest in the poorest and richest countries

Female labor strength participation is highest in some of the poorest and richest countries in the world. And it is lowest in countries with boilerplate national incomes somewhere in between. In other words: in a cross-department, the relationship betwixt female participation rates and GDP per capita follows a U-shape. This is shown in the scatter plot here.

To highlight continents, you can click on the continent name tags on the right panel. If you do this you will see that some interesting patterns emerge. Within Africa in that location is a negative correlation (the poorest countries have the highest participation rates), while in Europe there is a positive correlation (the richest European countries have the highest participation rates). Indeed, these correlations within high and low income countries seem to explain a big part of the U-shape that appears in the cross-section.

In the final department of this blog mail nosotros provide an overview of the forces that drive this correlation, borrowing from our companion weblog post on the determinants of female labor strength participation.

Female labor strength participation is college today than several decades agone

In terms of changes across time, the female labor force participation rate today is higher than several decades ago. This is truthful in the bulk of countries, across all income levels. The chart hither shows this, comparing national estimates of female participation rates in 1980 (vertical axis) and the near contempo year (horizontal axis).1

The grey diagonal line in this scatter plot has a slope of ane, then countries that have seen positive changes in female person labor strength participation rates appear beneath the line. As nosotros can meet, most countries prevarication on the bottom right. Indeed, in some cases, countries are very far below the diagonal line—in Qatar, for instance, there was a six-fold increase over the period.

On the aggregate, what does this imply for the global trend? The answer is non obvious, since some countries have missing data, and global trends are particularly sensitive to changes in large countries, such equally Bharat. In a recent do using statistical assumptions to impute missing data, the Globe Evolution Report (2012) estimates that in the period 1980-2008, the global charge per unit of female person labor force participation increased from l.ii to 51.8 pct, while the male person rate fell slightly from 82.0 to 77.vii per centum. So the gender gap narrowed from 32 percentage points in 1980 to 26 percent points in 2008.

An important point to note is that the chart includes all women in a higher place fifteen years of age. This means that the trends conflate changes across different population sub-groups (e.g. immature women, married women, older women above retirement historic period, etc.). Indeed, grouping-specific trends do not always follow the overall trends. Specifically, trends in labor strength participation amidst younger women are often dissimilar to the aggregate trends, notably in rich countries where participation expanded more often than not amongst the older, oft married female person population.

In many countries the historical increase in female labor strength participation took identify together with a reduction in participation among younger women, considering expansion was driven by women entering labor markets simply after attending college education. We discuss this in more detail below.

Some historical perspective

Female participation in labor markets grew remarkably in the 20th century

The 20th century saw a radical increase in the number of women participating in labor markets across early-industrialized countries. The chart here shows this. It plots long-run female person participation rates, piecing together OECD data and available historical estimates for a selection of early-industrialized countries.

As we can see, in that location are positive trends across all of these countries. Notably, growth in participation began at different points in time, and proceeded at different rates; nonetheless, the substantial and sustained increases in the labor forcefulness participation of women in rich countries remains a striking feature of economical and social alter in the 20th century.2

Nevertheless, this chart likewise shows that in many rich countries – such as, for case, the United states of america – growth in participation slowed down considerably or even stopped at the plow of the 21st century.3

Married women collection the increase in female person labor force participation in rich countries

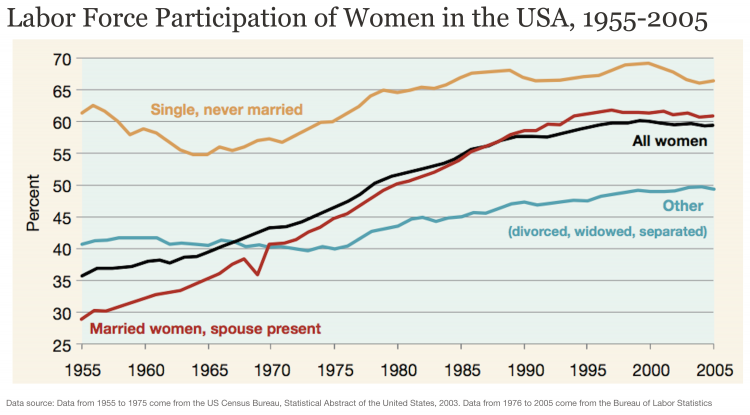

What practise we know near the characteristics of the women who drove this remarkable historical expansion of female person labor strength participation in rich countries? Every bit it turns out, the evidence shows that about of the long-run increase in the participation of women in labor markets throughout the final century is owing specifically to an increment in the participation of married women.

As an instance, the chart here shows female person labor force participation rates in the US, past marital status. As we can encounter, the marked upwardly trend observed for the general female population is mainly driven by the trend among married women. Heckman and Killingsworth (1986) provide evidence of similar historical trends for the Uk, Deutschland and Canada.4

Labor strength participation of women in the The states, by marital status – Engemann & Owyang (2006)5

Higher female person labor force participation often went together with fewer worked hours

The charts in a higher place provide show regarding the expansion of female person labor supply via college participation rates. But this is of class only one way of measuring marketplace supply. What about the number of hours worked? This is a relevant question since working hours for the full general population decreased substantially in rich countries every bit they increased their productivity throughout the 20th century.

The nautical chart here provides some clues. It shows several decades of changing average weekly hours worked for women in a selection of OECD countries. As we can see, most countries show negative trends, which is consistent with the trends for the population as a whole. However, some of these trends are still remarkable if nosotros take into business relationship the substantial increase in female participation taking place at the aforementioned time.

Consider the case of Spain: in the period 1987-2016, weekly piece of work in a principal job decreased from almost 39 hours, to nearly 35 hours; while participation rates for women increased from 32% to 54% in the same catamenia.

This is an of import blueprint: at the aforementioned time as more women in rich countries started participating in labor markets, at that place was oft a reduction in the boilerplate number of hours that women spent at work. In economics lingo: the 20th century witnessed a big increase in supply of female labor along the all-encompassing margin (number of workers), together with some reductions forth the intensive margin (hours worked per worker).

Available evidence shows that the upshot forth the extensive margin was much stronger. So in these countries at that place was an increase in the sum of female worker hours – that is, the total yearly hours worked per female worker increased across all female person workers.half dozen

Contempo developments

In recent decades the increase in women's participation has slowed or fifty-fifty reversed in some countries

In an earlier department we pointed out that since 1980, female participation in labor markets has increased in most countries; yet co-ordinate to the 2012 Earth Development Report the global trend only increased slightly over the same period – from 50.ii% to 51.8%.

If we focus on more recent developments, the ILO estimates show that the global trend is actually negative, mainly because of of import reductions in some globe regions. This is shown in the chart here.

Equally we can see, regional trends in recent years go in different directions. Notably, at that place accept been reductions in South and East Asia, and increases in Latin America. In the Middle Due east and North Africa there have besides been positive trends, simply this remains the region where female person participation rates are lowest.

You tin add countries and regions to the chart by clicking on the option ' Add country '. Or yous tin click on the 'Map' tab for an overview beyond all countries and continents.

Working women vs. Women in the labor strength

A taxonomy of labor supply

Before we move on to explore the determinants of female participation in labor markets, information technology is important that we dig deeper into the concepts. Nosotros have already said that labor force participation is defined as being 'economically active'. But what does that actually mean? Existence able to reply this question is crucial to understanding changes in female participation in labor markets, since women typically invest time on productive activities that do not count every bit 'market labor supply'.

From a conceptual point of view, people who are economically active are those who are either employed (including part-time employment starting from one hr a week) or unemployed (including anyone looking for job, even if it is for the offset time). Students who do not have a chore and are not looking for i, are non economically agile.

In the guidelines stipulated by the ILO, 'employment' besides includes self-employment, which ways that in principle, the labor forcefulness includes anyone who supplies labor for the product of economic goods and services, independently of whether they practice so for pay, turn a profit or family gain. This nautical chart from the ILO shows an overview of what counts and what doesn't towards producing 'economic goods and services'.vii

Loosely speaking, the guidelines stipulate that unpaid activities should be excluded if they lead to services or goods produced and consumed within the household (and they are non the prime contribution to the total consumption of the household).8 This frequently means excluding unpaid work on things like "Preparation and serving of meals"; "Intendance, training and instruction of children"; or "Cleaning, decorating and maintenance of the dwelling". The implication, then, is that even if the guidelines are followed closely to include all possible forms of economic activities, even in the informal sector, at that place will still exist an of import number of 'working women' who are excluded from the labor force statistics. And these exclusions are even more salient if nosotros consider that in many countries actual measurement deviates from the guidelines.

In many countries with poor chapters to produce national statistics, labor force participation is measured from population censuses, rather than from labor strength surveys particularly designed for that purpose.9 The consequence of this is that labor force statistics often exclude individuals who should be covered past the definitions higher up. Among the virtually of import exclusions are workers engaged in unpaid work.x

Given all of this, it is natural to wonder if the 'fundamental facts' would look different if nosotros used an alternative definition of labor supply. Let's try to break down the figures to understand any relevant differences betwixt 'labor supply' and other notions of 'piece of work'.

Breaking down the numbers

Formal employment

The first and nigh obvious line splitting the economically active population in a country is employment. The chart here plots female person employment-to-population ratios across the earth (national estimates earlier ILO corrections). These figures bear witness the number of employed women as a share of the total female population (in both cases, for women ages 15 or older).

To emphasize, hither we are leaving aside unemployment, and we are focusing on trends for employed women – who are, by definition a subset of the whole economically active population.

As we tin can run across, the trends are consistent with those for labor force participation: In the catamenia 1980-2016, the bulk of countries saw an increase in the share of women who are employed. This is what we would expect – it means that, by and big, the participation of women in the labor market was driven past employment, rather than unemployment.

(This chart shows the same variable but using ILO modeled estimates. These provide a shorter time perspective, only are more than accurate and consummate.)

Breezy employment

Let united states turn now to informal employment. As we mentioned above, the ILO guidelines stipulate that labor participation should include breezy employment. So this is some other of import line that, in principle, cuts across the economically active population.

The first point to note is that, despite the guidelines, in practical terms work in the informal sector is not e'er reflected in labor statistics due to measurement issues. And then an empirical study of economically agile women in the breezy sector remains a challenge. Nevertheless, some progress has been made on this front, and today many countries do report disaggregated figures for some forms of informal employment, mainly those relating to paid piece of work in non-agronomical economical activities. (You tin read more about measurement and definitions of informal employment in the ILO report "Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture show".) The chart shows these estimates.

The bars corresponds to the share of women employed in the breezy economic system, every bit a share of all women who are employed in non-agricultural economical activities. Years differ from land to country, and there is unfortunately yet insufficient information to explore time trends. Withal, as we can meet, the information does show that a large part of female employment around the world takes place in the informal economic system. In fact, in many low and middle income countries, the vast majority of women engaged in paid piece of work are in the informal economy. For women in Uganda, for example, almost 95% of paid work exterior agriculture is informal. In Greece, the corresponding figure is close to four%.

In this interactive data visualization you lot can see how the figures for women compare to those for men. The data suggests that in the majority of countries, women tend to work in the informal economy more frequently than men. And it is likely that this gender departure would be larger if we accounted for the informal agricultural economic system, for which information is not available. This is important because national sources of protection and support – also as legal and policy frameworks – tend to favor formal workers.eleven

Unpaid work

Let usa now accept a look at unpaid work. As we accept noted, domestic unpaid care work is an important activity which women tend to spend a significant amount of time on – and it is an activity that is typically unaccounted for in labor supply statistics. In the chart here we show just how skewed the gender distribution of unpaid intendance work in the household is.

The bars evidence the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid services provided within the household, including care of persons, housework and voluntary customs work. You can add countries using the push labeled ' Add together country '. And y'all tin can click on the 'Map' tab to go a cantankerous-country overview.

As nosotros tin see, gender differences in time devoted to unpaid care work cut beyond societies: All over the world, women spend more time than men on these activities. Yet there are clear differences when it comes to the magnitude of these gender gaps. At the depression end of the spectrum, in Uganda women work 18% more than men in unpaid care activities at home. While at the opposite finish of the spectrum, in countries such as India, women work 10 times more men on these activities.

This nautical chart provides a sense of perspective on the levels. In the MENA region, where the gap tends to exist largest, women spend on average over 5 hours on unpaid care piece of work per day, while men spend less than one hour.12

The forces driving modify

To recap: women all over the world allocate a substantial amount of their time to activities that are non typically recorded as 'economic activities'. What does this tell us about fourth dimension resource allotment and labor supply more generally? The answer is perhaps unsurprising. Female participation in labor markets tends to increase when the time-price of unpaid care piece of work is reduced, shared equally with men, and/or made more compatible with marketplace work.

You can find more details nearly the determinants of female labor supply in our companion web log post. Here we provide a quick overview of the key 'drivers'.

Maternal health

The various aspects related to maternity impose a substantial brunt on women'south time. And this is of course a biological burden uniquely borne by women. Moreover, motherhood is not but a burden in terms of time. It is also risky, and oft imposes on women a substantial burden in terms of health. Improved maternal health alleviates the agin furnishings of pregnancy and childbirth on women's ability to work, and is hence a fundamental commuter of female person labor strength participation.

Estimates propose that the historical decline in the burden of maternal atmospheric condition and the introduction of infant formula can account for approximately fifty percent of the increment in married women's labor strength participation betwixt 1930 and 1960 in the US.

Hither is a nautical chart that shows long-run trends in maternal bloodshed and female labor supply in the The states. You can read more than about maternal bloodshed here, and you can read more virtually its link to female labor supply here.

Fertility

Lower rates of fertility tin, in principle, gratuitous up a pregnant amount of women's time, hence allowing them to enter the labor strength more than easily. And this is of course independent of health complications – having children is very time consuming even when enjoying perfect wellness.

Indeed, there is strong prove of a causal link betwixt fertility (having children) and labor market outcomes (participation, employment, wages, etc.). In a recent study Lundborg, Plug and Rasmussen (2017)13 show that women who are successfully treated by IVF (in vitro fertilization) in Denmark earn persistently less because of having children. They explicate the turn down in annual earnings past women working less when children are young and getting paid less when children are older.

There are many other studies that find similar furnishings on female labor supply when there are exogenous shocks to fertility. And interestingly, there is evidence that women'south control over their own fertility is linked to career investments and subsequent changes in labor market outcomes (see, for example, Goldin and Katz 2002).fourteen

Here is a chart that shows the correlation between fertility and labor supply. Hither you tin read more most the bear witness supporting a causal link. And here you tin read more about fertility in full general.

Childcare and other family-oriented policies

The fact that fertility reductions atomic number 82 to higher labor force participation for women is certainly important from an empirical point of view. But information technology is obviously contradictory to promote female person agency while suggesting women should have fewer children. So information technology is helpful to consider other factors that brand employment compatible with childbearing, and thus broaden the choices available to women. Childcare and other family-oriented policies are prime examples here.

A cross-sectional analysis of data on public spending on family benefits shows that female employment tends to be higher in countries with college levels of public spending on family benefits.

Here you tin read more about the evidence behind family unit-oriented policies and female labor supply.

Labor-saving consumer durables

The consumer goods revolution, which introduced labor-saving durables such equally washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and other time-saving products, is another factor that contributed to the rise in married female labor strength participation in the last century.

Hither is a brief discussion of the correlation between hours worked in domestic activities and the availability of bones electrical appliances. And here you tin can find more details about an academic study that estimates the associated consequence on female labor supply.

Social norms and culture

Social norms and culture circumscribe the extent to which information technology is possible or desirable for women to enter the labor force. It is therefore not difficult to see why they play an of import function.

Socially assigned gender roles have ofttimes been institutionally enforced. And this is all the same the case today: In most countries around the world there are restrictions on the types of work that women can do.

From a historical indicate of view, at that place is evidence that social norms regarding economic gender roles accept long been around, and they are very persistent (see, for example, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn 2013).15

And all the same, despite social norms beingness persistent, there is also evidence that large and sometimes sudden changes are possible. Inquiry in this area shows that social norms and culture tin can exist influenced in a number of not-institutional means, including through intergenerational learning processes, exposure to culling norms, and activism such as that which propelled the women's movement.sixteen

Structural changes in the economy

Social barriers affecting female labor supply operate differently in unlike contexts. In detail, income levels and macroeconomic variables play an of import role. Every bit we evidence higher up, there is a U-shaped relationship between Gross domestic product per capita and female person labor force participation.

In low-income countries, where the agricultural sector is particularly important for the national economy, women are heavily involved in product, primarily as family workers. Nether such circumstances, productive and reproductive piece of work are non strictly delineated and the two tin be more easily reconciled.

With technological change and market expansion, however, work becomes more capital intensive and is ofttimes physically separated from the home, thus contributing to a decrease in women's labor forcefulness participation. Hence, in middle income countries, where there is often a social stigma fastened to married women working in blue-collar industries, "women's work is often implicitly bought by the family, and women retreat into the home, although their hours of work may not materially change."17

With sustained evolution, women make educational gains and the value of their time in the market increases alongside the demand-side pull from growing service industries. This means that in high income countries, the ascent in female person labor supply is characterized by women gaining the option of moving into paid, often white-collar work, while the opportunity cost of exiting the workforce for childcare rises.18

"

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-force-participation-key-facts

0 Response to "What Group of Women Was Initially Targeted to Join the Labor Force?"

Post a Comment